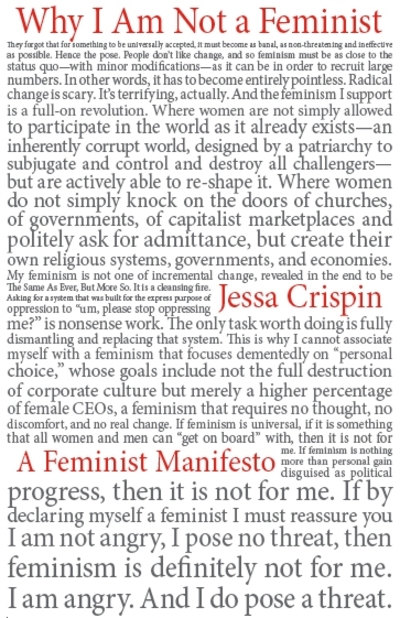

Jessa Crispin has written this manifesto with a specific intention: to incite her readers to move away from their lazy, notional, individual feminism back towards the good ole’ ways of radical action. Unfortunately, her attempt to do this comes across as lazy, notional and self involved. Crispin begins her polemic by clearly outlining her reasons for rejecting feminism, finishing with her particular distaste for the “all about me” flavour of the modern movement. The irony of following this with 150 pages of her individual opinion on modern feminism, is so blatant one can’t help but wonder if it is intentional satire. This sets the contradictory tone for the book, one which repeats the same logical fallacies chapter after chapter.

While reading this self-proclaimed manifesto, I found myself rolling my eyes at the same arguments. It is because of this constant repetition, in the name of efficiency, criticisms of this book have been divided into sections.

SOME ARE BORN FEMINIST, SOME BECOME FEMINIST, AND SOME HAVE FEMINISM THRUST UPON THEM

Crispin wants a feminism that is unapologetically angry and poses a threat. I certainly understand the premise for this, I am an angry feminist myself. But feminism is linear and sometimes the people you are scaring off, are the future champions of your cause.

When I was 16, I was categorically NOT a feminist. When I was 17, I agreed with the concepts of gender equality, but still wouldn't call myself a feminist. By 18, I was onboard with the term, but not actively involved in the movement. Here I am at 24, and all I do is feminism. All I do is research, organise, write, and rant. But I wasn't born that way, it was something I had to come to in my own time. Part of that process was buying T-Shirts, and googling to see if my favourite celebrities were feminists. I have every intention of dedicating my life to feminist cause, but I can’t help but wonder: if it was only angry, threatening women identifying as feminists when I was young, if only women interested in the complete dismantling of the world as we knew it identified as feminists, would I be where I am today? No.

For someone so furious with the distance young feminists create between themselves and radicals, Crispin's decision to alienate young feminists, and young women showing an interest in feminism is all the more confusing. Sure, there is no direct link between girls worshipping Beyonce or wearing feminist T-shirt and the decision to partake in collective radical action. That said, I am yet to meet a feminist who woke up one day and decided to radicalise with no previous interest in even the most superficial elements of the movement. If you allow no space for women to have less than radical feminist views, you create a very hostile and divise environment for young women who may want to be feminists.

BACK IN MY DAY: A LOVE LETTER TO THE SECOND WAVE

I can comfortable say that if you were talk to most young women about why they have grievances with second wave feminism, their answers will not be the same as the ones suggested by Crispin in this book.

There is an assumption weaved the whole way through this manifesto, that young feminists distance themselves from their second wave radical past because of body hair and militant anger. The truth is, while I am thankful to the work of the women in the second wave, I distance myself from that kind of feminism with valid cause. It has nothing to do with body hair and bra burning and everything to do with the unforgivable treatment of minorities within the movement. I know many young women feel the same. If you want to be radical and hold on to that past, then we can disagree, and in my opinion that doesn't make any of us less of a feminist. Rationally, I can understand the arguments that Trans Erasing Radical Feminists and Sex Work Erasing Radical Feminist’s put forward, but I categorically reject them and do not wish to be associated with them. My rational understanding of the arguments, is not akin to the incessant yet weak defence of these views executed by Crispin. It is the erasure of minority women, which Crispin is so concerned about in her second chapter, that is a cornerstone for essentialist second wave feminism. It is this erasure that causes me to recoil from the association, not Birkenstocks and dirty hair. I do not care what men think of me, but I certainly do care what black women, and transwomen, and sex workers, think of me. Germaine Greer, for instance, is someone whose work I feel very strongly about. As an Australian feminist, The Female Eunuch, is a foundational text for much of my work. And yet I distance myself from her, not as a response to her position that true feminism cannot be realised without a communist revolution, but because her unforgivable vitriolic stance regarding transwomen. Crispin’s rejection of the universal feminist goal paired with her nostalgia for the second wave is completely nonsensical.

YOU DON’T KNOW US: THE ATTACK ON MILLENNIAL FEMINISTS

The constant, belligerent, unfounded criticism of young feminists was almost enough for me to discount this book in it’s entirety. I am a working feminist (although as my research focuses on bettering women’s position within the existing patriarchal system, I am not really doing anything by Crispin’s standard). Crispin’s condescending and patronising tone toward young women like me was maddening and demonstrated a complete lack of rigour in the research behind this book. One can only assume that Crispin did not take the time to engage with any young feminists at all. Perhaps she looked at click-bait and used that to found her argument, her decision not the name name’s makes it impossible to tell. To accuse young feminists of using the movement as an accessory, is an insulting generalisation. Furthermore, it is a harmful one. The proclamations made in this book not only alienate young feminists (even radical ones) but erase the valuable work that we are doing. Her lavish assumptions do not help the progress of the movement, and only work to serve her own agenda.

She dismisses modern feminism for prioritising opinion and personal narrative over theory or even fact, and yet, I’ve referenced more feminist theory over cocktails on Saturday night than Crispin does in this entire publication. Moreover the exclusion of references to the women whose theories she lightly references was a point of major concern. Crispin’s decision not to provide a platform for other feminist thinkers, weakening all of her arguments, and to be quite frank allowed much of her book to preoccupy itself with non-issues and distractions such as armpit hair and Taylor Swift. Crispin polemic comes across as under-theorised and confused due to her unwillingness to credit the thinkers behind so many of the arguments she tries to lean on. Referencing Kimberlé Crenshaw for introducing the term intersectionality in 1989 would have barely impacted her word count. It clearly didn’t impact mine.

THE RULE OF CRISPIN’S ELITE FEMINISTS PROGRAM

According to Crispin, everyone is human and everyone is capable of mistakes. Feminists aren’t perfect, and in the case of radical feminists such as Andrea Dworkin, there is more to be gained from overlooking mistakes and learning from their larger philosophy. I cannot say that Crispin’s leniency and forgiveness stretches so far as to cover anyone who does not unflinchingly identify with her “cleansing fire” brand of feminism. Crispin states that "we speak for women instead of listening to them." This reads more as a self-diagnosis as she groundlessly pontificates about the views of women for most of the book. By Crispin’s diagnosis, if you are focused on making money, you are the enemy. If you are not ready and willing to give up everything touched by the patriarchy at this very moment, you are the enemy. If you shave your legs, guess what, you are the enemy. There is no sympathy or understanding for those who are not in a position to leave their ‘comfortable’ life and step into the fringe. And while Crispin says that personal details about feminist authors are always used to discredit their work, there is an unmissable hypocrisy in a white woman whose career has been funded by publishing in male-run, male-serving newspapers and magazines, telling other women that sacrificing their radical feminism to get ahead in the male world is just not good enough. To the single mothers who need to work for the man to provide for their children, to any person with a physical or mental disability who faces additional obstacles to participation in the movement, to any woman who has grown up poor and rightfully wants to create a better life for herself, there may not be space for you in Crispin’s “cleansing fire” feminism but there is space for you in mine.

WHAT MANIFESTO?

Call me crazy, but when I pick up a piece of work that refers to itself as a manifesto, I expect to see some kind of statement of intention, aim, or goal. Crispin spends so much of her small book criticising the way things are, that she has no room left to suggest how we get things to where they should be. At it’s best this book is food for thought. At it’s worst it is a colossal and insulting waste of time. If you are truly looking for something worthwhile to read, flip to the author’s notes at the back of this book and read the works by the feminists she credits instead. It’s a much better use of your time.